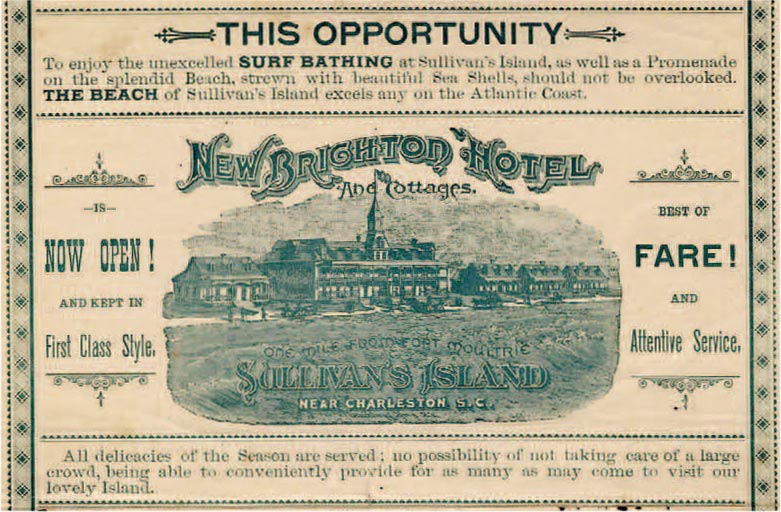

A luxury resort hotel right in the middle of Sullivan’s Island? And with a casino, performance hall and its own sources of water and natural gas? Yes, this actually happened.

Built in 1884, the New Brighton Hotel rivaled any resort on the East Coast at the time. Its existence was intended to spur the dawn of a new era, a post-Civil War identity that capitalized on tourism. The site between Station 22 and 22½ was donated by the town of Moultrieville for that purpose, and the 11-acre tract was given the alluring name “Ocean Park.” Boston businessman J.F. Burnham, “a Northern gentleman of means,” paid construction costs and owned the buildings for more than a decade. The ownership changed hands in 1896 when the McCullough family of Columbia bought the property and renamed it the Atlantic Beach Hotel.

The New Brighton was not the first hotel on Sullivan’s Island. Even before the Civil War, the village of Moultrieville was one of the most popular summer resorts in the United States, with several boarding houses and a well-known hotel called the Moultrie House. But the concept of luring wealthy northerners took on new importance after the war, and the region’s struggling economy yearned for the attention. At the time, The News and Courier reported that “the public may rest assured that Charleston will become the great summer resort of the South.” Hundreds of local jobs were created with the New Brighton’s construction alone, and, as an incentive for investment, the hotel’s owner was exempt from paying property taxes for the first five years.

Atlanticville, as the middle of the island was then known, was on the outskirts of the island’s established residential area, so there was plenty of room for the multiple buildings that comprised the resort. Besides the grand, 112-room hotel, with its Victorian turrets and towers, there were several two-story guest cottages, each with eight to 10 rooms equipped with “speaking tubes” so guests could contact the hotel’s office. The resort’s property ran from the ocean front to the “back beach,” with horse stables and fowl houses at the far rear of the compound. A private rail line for use by guests only ran to the hotel from the ferry at the southern point of the island.

The main building sat on 7-foot-high brick pillars. A 65,000-gallon cistern and a wine cellar made of solid brick were at ground level. Dormer windows and a mansard-style roof topped off the three-story structure. The hotel’s interior design took full advantage of the prevailing sea breeze, using wide hallways to keep the air circulating and second-story rooms with French doors that opened onto private balconies. The dining room, on the first floor, was kept cool with its 18 windows and 15-foot ceiling. A wide veranda facing the ocean ran the entire 120-foot length of the building.

The hotel’s furnishings were extravagant, and guests had the modern conveniences of gas lighting and electric bells in their rooms to summon the front desk. The lavish garden behind the hotel was trimmed with Bermuda grass, ornamental trees and shrubbery, emulating prominent resorts in the North. Roy Williams, author and long-time islander, believes even the Brighton Hotel’s name was meant to evoke the image of “the most fashionable resort in England.”

The casino, in a separate building facing what is now I’On Avenue, featured private billiard rooms, pool rooms and saloons. Additional guest rooms were on the floor above. A performance hall with a seating capacity for 500 featured nationally-acclaimed entertainers, including the renowned Reaves American Band and the Vienna Female Orchestra. Because of the first-class entertainment, Charleston residents were among the patrons of the performances. In fact, one advertisement in the local newspaper informed Charlestonians that they could take the ferry over to the island, enjoy a performance and return home that evening for much the same cost as attending one at the popular Academy of Music downtown.

Two bathhouses – one for men and one for women – were on the premises. Since most people did not own bathing suits in those days, they were provided for guests. A wooden walkway led out to the beach so guests wouldn’t have to climb over the sand dunes to get to the ocean.

The hotel survived several hurricanes but met its demise in a fire in January 1925. By then, it was operating as the less illustrious Atlantic Beach Hotel. Legend has it that a bootlegger who was searching the bushes near the casino for his hidden supply accidentally ignited the brush, causing a fire that spread to the main building and cottages.

By that time, the allure of Sullivan’s Island’s main attraction had faded, due in large part to the popularity of newer resorts in Florida. But standing on the wide beach today, with the dunes and lush maritime forests at your back, it’s not too hard to imagine the excitement experienced by guests of the New Brighton Hotel.

Leave a Reply