Concrete evidence of the key role Sullivan’s Island has played in U.S. history can be found on a map of the city or by taking a short drive from one end of the island to the other.

The names of the streets that crisscross the island reflect the people and events that combined to help settle a continent, forge a nation, survive a major internal conflict and emerge from two world wars as the most powerful country on Earth.

Sullivan’s Island took its name from Florence O’Sullivan, who traveled to the American Colonies from Ireland in 1669 and was elected to South Carolina’s First Provincial Parliament three years later. In May of 1674, he was placed in charge of a signal cannon that he was to fire as a warning to settlers at Charles Towne when ships entered the harbor. For more than two-anda- half centuries, until the end of World War II, Sullivan’s Island played a key role in the harbor’s defense.

Many of the island’s streets honor its place in American history. For example, early in the Revolutionary War, the British tried to take Charleston by land and sea, bombarding Fort Sullivan, commanded by Gen. William Moultrie, from the harbor and attempting to advance across Breach Inlet from Long Island, now the Isle of Palms. The British effort fell short on both fronts, thanks in part to the heroics of soldiers whose names now grace street signs on Sullivan’s Island.

Sgt. William Jasper risked life and limb under heavy fire to replace the flag flying over the fort and help maintain the morale of its defenders. Today, the main street that runs from the center of the island to the Thompson Memorial Bridge over Breach Inlet is Jasper Boulevard.

The bridge is named for Lt. Col. William Thompson, who commanded the regiment of sharpshooters that kept British troops from crossing the inlet and attacking the fort by land. Thompson Avenue, which runs from Station 18 Street to Station 13 Street, also bears his name.

Star of the West Street, on the western tip of the island, harks back to the Civil War. From across Charleston Harbor on Morris Island, Citadel cadets fired on The Star of the West, a ship trying to supply the Union troops at Fort Sumter. Citadel Street runs from Middle Street to Poe Avenue.

Sullivan’s Island remembers 20th century conflicts with Conquest Street, at the west end, and Quarters Street, which connects Jasper Boulevard and Middle Street and commemorates the Army personnel quarters in use during two world wars. Marshall Boulevard, which runs along the ocean near Breach Inlet, is a nod to Col. George Marshall, who commanded the Army receiving station for troops preparing to be shipped overseas during World War II.

Several Sullivan’s Island streets bear the family names of local residents killed in action during the two world wars, including Harvey, Brownell, Brooks, Keenan, Iziar and Williams.

Seminole Chief Osceola, though technically an enemy of U.S. military forces, has a Sullivan’s Island street named in his honor, a corridor running from Middle Street almost to the west end of the island. He was held prisoner at Fort Moultrie, the former Fort Sullivan, until his death in 1838.

American poet, author and literary critic Edgar Allan Poe, who served in the U.S. Army and was stationed on Sullivan’s Island in the 1820s, left his mark on the island.

Gold Bug Avenue and Raven Drive are references to a short story and a poem he wrote. Poe Avenue runs from Station 16 Street to Station 18 Street.

The name of another Sullivan’s Island street is only indirectly related to military ventures. Col. Jacob Bond ‘Ion, a Mexican War veteran, owned a house on the island that was a popular meeting place for officers stationed at Fort Moultrie. I’On Avenue, spelled differently but nevertheless honoring this former island resident, runs parallel to Middle Street. Florence Street, between Middle and Poe, honors Florence O’Sullivan.

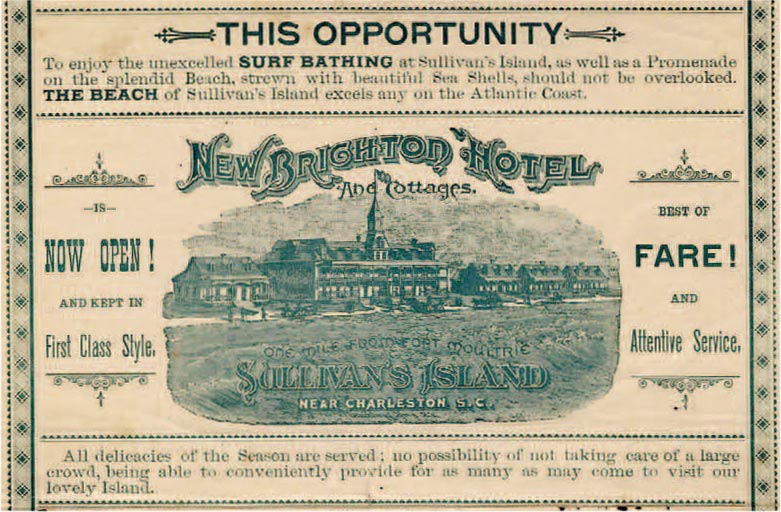

Some street names are a reminder of the island’s non-military past. For instance, early in the 20th century, Charleston residents wishing to travel to the Isle of Palms had to take a ferry across the Cooper River to Mount Pleasant and a trolley to Sullivan’s Island and over Breach Inlet. The trolley stopped at numbered stations on Sullivan’s Island, located at streets that still bear the names of those stations, from Station 32 Street near the inlet to Station 10 Street at the west end of the island.

Other street names on the island are simply descriptive: Back Street is home to a row of back beach cottages; Cove Avenue is near a part of the harbor known as The Cove; myrtle trees adorn Myrtle Avenue; Atlantic Avenue is near the ocean of the same name; and Sea Breeze Lane, on the narrow part of the island, no doubt sees and feels its share of sea breezes.

And then, of course, there’s Middle Street, which runs down the middle of the island, from beyond Fort Moultrie at the west end, all the way to where Jasper Boulevard becomes the Thompson Memorial Bridge, traversing Breach Inlet to the Isle of Palms. Along its journey, it comes within hailing distance of almost every other street on an island destined never to forget its storied history.

Why are the streets called “stations”? What’s the history of that?

It seems that the streets named Station were named for trolley stops.