Throughout the centuries, we’ve looked to artists to tell our tales and capture a part of history on canvas. Immortalizing moments and citizens through paint and brush strokes, creatives are truly the keepers of the flame – illuminating the noteworthy individuals who came before. Often, artists can shine a light on dark times and pay homage to unsung heroes whose stories are heavily marked by triumph and tenacity.

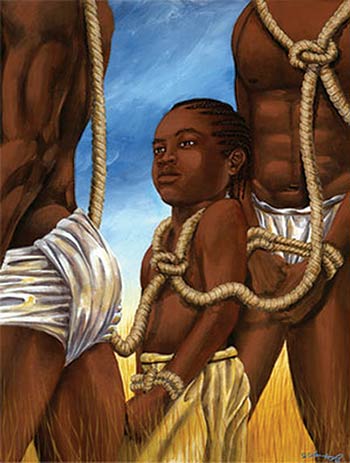

In 2002, artist Dana Coleman captured the unbreakable spirit of a 10-year-old slave girl he never met. Ripped from her home in 18th century Sierra Leone, forced into a life of bondage, a piece of her has now returned to her place of origin. Coleman’s painting proudly hangs in The Sierra Leone National Museum, while a giclée can be found on Sullivan’s Island at the Fort Moultrie National Monument.

A chance meeting at Boone Hall Plantation with historian Joseph Opala would set Coleman on an artistic journey commemorating one little girl’s tumultuous voyage from Sierra Leone to Sullivan’s Island. Opala was working on a project that directly linked a girl named Priscilla to two local citizens: Thomalind Martin Polite, her seventh-generation granddaughter, and Ed Ball, a writer whose ancestral family records revealed their purchase of Priscilla in 1756. Searching for an artist to memorialize one of the most well-documented slave lineages in history, Opala enlisted Coleman.

The Awendaw native poured himself into the history of Priscilla – searching the web, diving into research and visiting local libraries to check out books on the slave trade to uncover just what that harsh journey across the Middle Passage entailed.

What he discovered was that the Charleston area was America’s main point of entry for slaves brought over in the 1700s. Ships carrying men, women and children across choppy waters were often breeding grounds for measles, smallpox and cholera. Many didn’t survive the cruel journey, but Priscilla did, arriving on a ship named the Hare, and was sold to Mr. Ball of the The Comingtree Plantation.

“I wanted to show her from the perspective of the viewer looking up at her,” said Coleman. “I wanted to depict her as a survivor, with a strong confidence, with her head up as if to say, ‘Bring it!’”

In order to fully capture both the accuracy of the time period and the appropriate mood, Coleman did 15 sketches over the course of three months, finally deciding on one that would exude the strength of this confident 10-year-old. Since no portraits or photographs of Priscilla existed, Coleman studied the image of young Sierra Leoneans, utilized his own children as models and even used Thomalind Martin Polite’s photos from childhood in order to capture the perspective likeness of Priscilla.

“Opala explained this piece of art would live on long after I’m gone and appear in history books for years to come, so it was very important for me to get it just right,” said Coleman. “To know that I was able to paint Priscilla, the most complete documented case of any slave in history, is a great honor.”

Multiple publications, including The New York Times, took note of Coleman’s talent.

“It was so touching to learn about the courage of this little girl,” said Coleman. “I can’t imagine the fear of being taken from your home and forced into the belly of a rocking boat with strangers. Millions died on that journey, but Priscilla survived.”

In Coleman’s painting, Priscilla is tied by coarse rope to two other slave men, yet she doesn’t appear to be cowering in fear. Her shoulders are back, her eyes are open and a sky of bright blue can be seen in the background – perhaps a nod to the irrepressible light within her.

“I loved doing it and would do it again if the opportunity came up,” said Coleman, who, after capturing the likeness of Priscilla, was inspired to paint the sights and scenes he saw as a youth growing up in Awendaw.

In his series, “Colorful Expressions,” Coleman paid homage to those in his community committed to spreading joy and proudly keeping the soul of their heritage in full bloom. Dancers draped in brightly-hued fabric, singers belting out spiritual hymns and harvesters proudly clutching the bounty of their gardens all make appearances in this collection of Gullah-Geechee culture.

While Coleman has painted the magic of Lowcountry sunsets and serene herons resting in beds of marsh grass, his time spent crafting “Priscilla” is something he cherishes most of all. Knowing his creative expression has brought such joy and closure to a family and a nation continues to fuel his artistic journey. By showcasing the fortitude and inner strength of a child, he has revealed a bit of bravery and grace of a time in our past plagued with forced migration, sorrow and brutality.

“When I completed the painting of Priscilla, I felt like I overcame a mountain,” said Coleman. “The accolades I received are great, but the biggest reward comes with knowing I was able to contribute in some way to this woman’s legacy.”

By Kalene McCort

Leave a Reply