“Sullivan’s Island – A more uncomfortable place could not be found.”

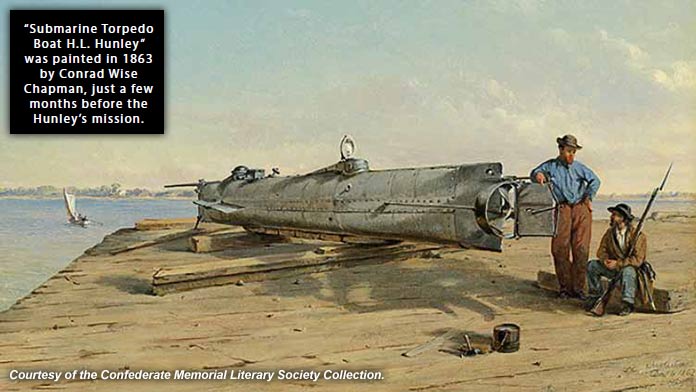

These are the words of Lt. George Dixon, commanding officer of the H.L. Hunley, the Confederate submarine whose base of operations was at Breach Inlet in 1864. In fact, Dixon and his crew of seven men slept at a boarding house in Mount Pleasant and made the commute mostly on foot to work each day – and then back home afterward.

But the island’s lack of comfort was likely not the sole reason for the men lodging elsewhere. Much of that decision may have even been about physical conditioning.

Operating their little submarine required arduous work, and the men were required to be in top-notch condition. They would be working long hours, turning a crank constantly to propel their craft through several miles of ocean currents to reach their target.

The original plan wasn’t to deploy from Sullivan’s Island. After all, the Union blockade was positioned mostly at the mouth of the harbor. But rather than penetrate the blockade’s center and risk being picked off by Union fire, an alternate strategy involved attacking the outermost vessels first, where it was least expected. Plus, hiding the sub at such an isolated and remote location on the north end of Sullivan’s Island helped to keep it a secret from curious civilians.

So, in January 1864, the Hunley was moved from a dock in Mount Pleasant to the Breach Battery – also known as Battery Marshall – on Sullivan’s Island. The ocean view was perfect – the Union ships could be seen anchored four miles off the beach, a relatively straight path from Breach Inlet for an attack on one of them. A night deployment would provide the Hunley a cover of darkness for protection, and the lights onboard the Union ships would guide the little sub right to its target.

But there was a lot of work to be done before any of that could happen. Five nights a week, the Hunley’s crew took their boat out on maneuvers, practicing diving and surfacing, often in Cove Creek, behind the island. For drills at sea, a calm night with relatively smooth water and an outgoing tide provided the best conditions. But it was winter, and the weather can be brutal, even in Charleston, so there were no guarantees. At one point, the Hunley actually had to remain dockside at Breach Inlet for two weeks due to heavy fog and rough seas.

If the outgoing tide would aid the crew when leaving port, what about getting back to the island afterward? As any kayaker can attest, rowing against the strong currents of the ocean is no easy task. More than likely, there were times during exercises at sea when the boat didn’t make it back to the inlet and instead ran aground elsewhere on the beach. Evidence that this probably happened is in the records, indicating that a support boat eventually was assigned to Battery Marshall, probably for towing the sub back to the dock when it was beached.

And how long could the boat stay submerged without the crew succumbing to asphyxiation? After all, the only air available to the men was what was in their cramped space when they went underwater. So a test measuring both physical and mental endurance was conducted in the creek, not far from Breach Inlet. During the test, the Hunley was underwater for so long that the soldiers at Battery Marshall assumed all was lost. When the boat resurfaced more than two hours later, there was only one soldier dockside to greet the crew.

For the last few days before the Hunley’s historic deployment on Feb. 17, the crew may have slept at Battery Marshall, possibly to spare them their exhausting commute from Mount Pleasant. However, more than likely it was because Lt. Dixon would be watching for just the right weather conditions to embark on the mission.

The ending to the story is well-known. The submarine was successful in bringing down its target. By flashing a blue light from a magnesium lantern to their comrades on shore, the crew of the Hunley signaled that their mission was accomplished and that they were returning to Sullivan’s Island. Fires at Battery Marshall were stoked to guide them. However, the Hunley didn’t make it back. Its whereabouts were unknown for well over a century. When it was finally discovered in 1995, the submarine’s original trajectory from Breach Inlet guided researchers to pinpoint the area of ocean floor to search.

Some folks wondered if Hurricane Hugo’s bull’s-eye path may have stirred things up enough to help find the Hunley. Although it wasn’t likely, that possibility is what kept researchers looking a few miles off the shores of Sullivan’s Island. But the sea doesn’t easily give up her secrets, and this is one that continues to intrigue us 21 years later.

by Mary Coy

Leave a Reply